Friends, I am new to Substack, so thank you for being patient while I work out how to do what I would like to do!

And what is that? Just to add pieces from time to time. No schedule, and therefore no payment required. If you wish to subsidise me, then by all means be so kind, but everyone sees everything. At least that’s how I intend it now.

I’d like to welcome you, and point out for those who do not already know, that there is a very large library of material at my website channelmcgilchrist.com. There is a members’ area, but the majority of the articles by myself and others, the enormous number of videos and podcasts, the daily poetry readings which I recorded in the first year of lockdown – therefore 365 of them – are open to all-comers. Please go and browse whenever you feel inclined. Settle into a library chair with a cup, or a glass, and (with luck) enjoy what you find there.

I am assuming, rightly or wrongly, that most of you, being self-selected, will be a little familiar with my work, so I will not do what my friend Jonathan Rowson calls ‘McGilchrist 101’. If you are completely new to my work, I strongly suggest beginning with Channel McGilchrist.

In what I write I will make free use of The Matter With Things, and move about within it and add to it.

And so straight to today’s topic.

People often ask me what they should do to redress the balance between the brain hemispheres. The first step to recovering anything is to be aware of how much you are missing by your way of being in the world. So the first question to ask yourself should be: what does my particular take on reality exclude from my vision? There is of course a paradox, in that if you can’t see it, how can you know what it is? But there are ways to avoid being trapped. One is to stop believing that what people at other times and in other places thought was due to their ignorance. Experience show us that truth is rarely pure and never simple. We know differently, not necessarily more or better; and confining ourselves to just one way of looking at things may obscure others from our sight altogether.

As you know, I believe that attention, the kind of attention we choose to pay, and indeed whether we attend at all, wholly alters what we discover in the world we come to know - which is of course all that any of us can know. Attention is, then, a creative (or destructive) act and therefore necessarily a moral act. Pure attention has been likened by Louis Lavelle and Simon Weil to love itself.

Because of the asymmetry in their mode of attention, each hemisphere has a different take on everything – including on its relationship with the other hemisphere. This is best illustrated by the story from which The Master and his Emissary takes its title. There was a wise spiritual Master who looked after a small community so well that it flourished and grew. Eventually the Master realised that he could not take care of all his people’s needs on his own; more importantly, he realised that there were certain matters that he not only could not, but must not, become involved in, if he were to preserve his overview. He therefore appointed his brightest assistant to go about and do work on his behalf. Though bright, this emissary was not bright enough to know what it was he didn’t know. He became arrogant and resentful of the Master: ‘What does he know?’, he thought. ‘I’m the one that does the real work round here, I’m the one that really knows.’ And so he adopted the Master’s cloak, and pretended to be the Master. The emissary not knowing what it was he didn’t know, the community declined, and the story ends with the ruin of the community, including both the Master and the emissary.

Not ignorance, but ignorance of ignorance, is the death of knowledge. The right hemisphere, however, knows what it is that it must not get involved with. In the story that is why the Master (the right hemisphere) appoints the emissary in the first place.

You may imagine that, when I say things like ‘the left hemisphere does not seem to know what it is it does not know’, I am speaking purely figuratively. But I am not. There are plenty of examples – particularly vivid in the case of split-brain patients, but often seen in more common situations such as stroke – in which the left hemisphere not only clearly does not know what it is talking about, but behaves as though it knows perfectly well. Its manner is confident and unhesitating, even when it is talking about something of which it knows absolutely nothing. By contrast, the right hemisphere tends to be hesitant, tentative and flexible, even when it is entirely right.

There are a number of reasons for this. The left hemisphere is aware of much less of what surrounds it – ‘sees less’, in all senses, than the right. It is less tolerant of ambiguity and tends towards exclusive, ‘either/or’, thinking; the right hemisphere is more inclusive, inclined to ‘both/and’ thinking. This is imaged in the relationship of the two hemispheres: the right hemisphere communicates more, and more quickly, with the left hemisphere than the left hemisphere does with the right; and the left hemisphere communicates more within itself, while there are ‘more bilateral interactions between hemispheres for the right hemisphere’. The phenomenological world of the left hemisphere is more self-directed, enclosed, self-validating – in thrall to its theory; the world of the right hemisphere more open to new information, the bigger picture, and what is actually the case, regardless of what the theory might suggest. All of which adds up to the right hemisphere seeing the relationship between the Master and emissary as co-operative, and requiring both parties, as the Master does in the parable; whereas the left hemisphere, like the emissary, sees itself as not needing (in truth it does not understand) what it is the Master knows. It’s a good servant, but a very poor master.

Why am I reminding you of this? Because the left hemisphere doesn’t know what it is it doesn't know. And this is where we come to metaphors.

As Lakoff & Johnson have explained at length, all language is metaphorical. It is not just a decorative turn in poetry, but it is ‘poetic’ in the original meaning of that word (from Greek poiesis): it makes things. Our world is built on metaphor, and nowhere is this truer than in science and philosophy. This means two things: we cannot under any circumstances dispense with metaphor; and since the metaphor we choose governs what is illuminated for us, and what is cast into the shadow, we had better be very careful about the metaphors we use.

But we are not. Everywhere we liken everything, the world, nature and ourselves, to the machine. The machine is the tool of the left hemisphere and its raison d’être, power. Arguably, the only things in the universe that are machine-like are the few lumps of metal we have created, mainly in the last 300 years. In the past we likened objects of experience to organic entities — a family, a tree, a stream. For important reasons, I favour the stream of life. All things flow — and perhaps especially, and in so many senses, life itself.

About 100 years ago, physicists had to come to terms with the fact that the machine metaphor or model was inadequate to describe what they were finding out about the world of inanimate matter. Biology, the science of life, however, was left behind — until recently. There is now a revolution going on in biology whereby it is becoming at last undeniable that living beings are nothing like machines. Nor are we ‘survival machines – robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes’. Almost everything is wrong with this unfortunate sally. Organisms are blatantly not ‘machines’ at all; nor are they just, or even, ‘survival’ machines; there is no sense in which even a single cell can be said to be a robot; nor is it ‘programmed’, never mind ‘blindly’ so; nor are genes ‘selfish’; and organisms routinely dispose of and rearrange substantial parts of their genome, some to an extraordinary extent.

In The Matter With Things I explore the inaptness of the machine metaphor in biology at some length, in Chapter 12, entitled ‘The science of life: a study in left hemisphere capture’. It’s 70 pages long on its own, and the argument is incremental, but let me just quote a few paragraphs out of context, because some of the substance may not be known to every reader, and sets one thinking. There is much more to say, of course, and there are comprehensive notes of all sources, and further excursive discussion in the notes. I may in time put up more of this chapter if people are interested.

Some brief thoughts from Chapter 12

If a cell is placed in a slightly acid medium, its mitochondria break up into small spherical beads. But, amazingly, on return of the cell to a normal medium, they merge again into strings, and eventually take on once more the appearance and internal structure of normal mitochondria. Further, let us suppose you cut a developing limb bud out of an amphibian embryo, shake the cells loose from each other, and then allow them to aggregate once more into a random lump. You then replace the random lump in the embryo. What happens? A normal leg develops. The form of the limb as a whole dictates, according to Lewontin, the rearrangement of the cells:

Unlike a machine whose totality is created by the juxtaposition of bits and pieces with different functions and properties, the bits and pieces of a developing organism seem to come into existence as a consequence of their spatial position at critical moments in the embryo’s development. Such an object is less like a machine than it is like a language whose elements … take unique meaning from their context.

Or like a dynamic field. ‘If the organism was simply its substance we would not be able to recognise it from one day to another’, wrote Lawrence Edwards, an expert in plant morphology. ‘Yet its being and largely its form are invariant from one moment to another, and from one day to another. The form can live within the flux. Something greater than the substance takes it up, moulds it, uses it, and then casts it away.’

Again, unlike in a machine, no two limb buds in a developing embryo are ever exactly the same; the buds of formative, mesenchymal cells develop each in their own way. The result is in each case a normal, fully formed limb of the kind dictated by its position. But not just its ‘predestined’ position: the same cell group in a limb bud can nonetheless, though destined to form the pattern of, say, a right limb, give rise to the mirror image, a left limb, with the opposite symmetry, simply by being transplanted to the opposite side of the embryo.

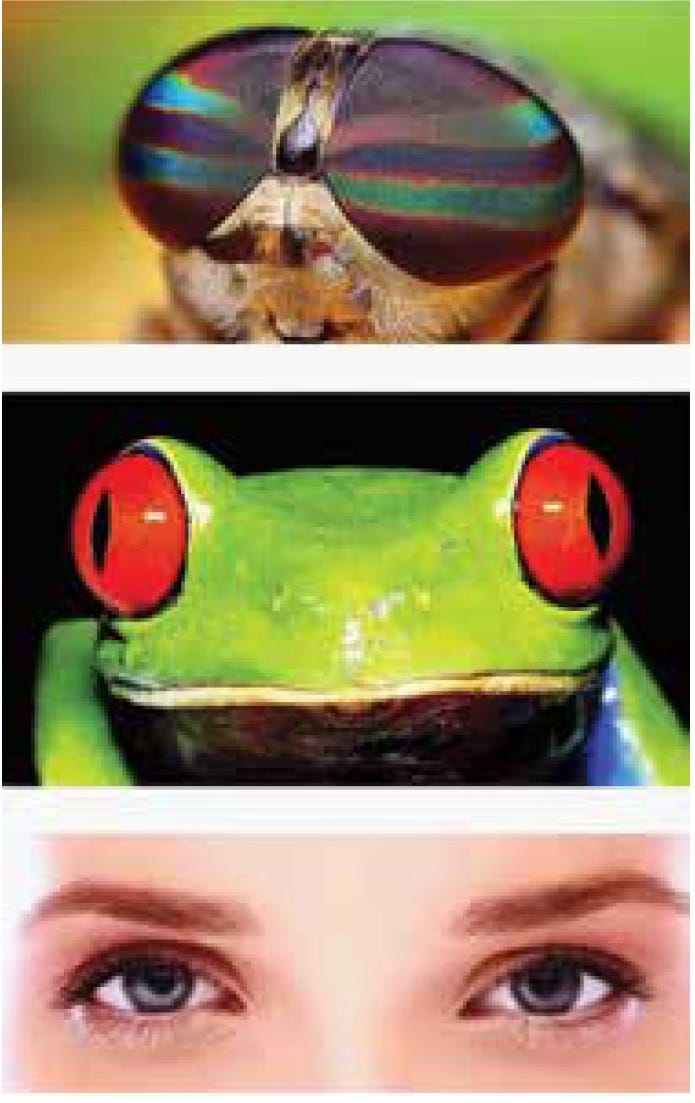

Another example of the whole somehow overruling the parts comes from fascinating experiments on the fruit fly, Drosophila. The absence of a gene, homologous to Pax6 [which plays the critical role in the development of an eye, occurring in almost identical form in a range of species, enabling the development of a fly’s eye, a frog’s eye or your eye, though the types of eye, how they are structured, and how they function, are very widely different] causes the fly to develop without eyes. However, if such flies are interbred, they have been found soon to develop eyes – despite not having the gene in question. Indeed, after ‘knocking out’ (disabling) both copies of a gene that had a normally important role in the development of a mouse, molecular biologists found that in many cases the mouse seemed unimpaired, and functioned normally. In certain strains of mice, mutations in the Kit gene cause white patches on the tail and feet; if a mouse has one normal Kit gene and one mutated one, it will have the patches. Yet some of the offspring of such mice, who inherit two normal Kit genes, still have the white tail. Resistance to viral infection in a nematode worm was achieved by some of the population having DNA that produced a viral-silencing RNA sequence; when cross-bred with worms who lacked this DNA, some of the offspring inherited the antiviral mechanism and some didn’t. All as one might expect. However, subsequent generations inherited the antiviral mechanism even if they lacked the required DNA. This non-DNA inheritance was followed successfully for 100 generations.

Similarly ‘adaptive mutation’ dictates that if a strain of bacteria is unable to utilise lactose, and is placed in a lactose-rich medium, 20% of its cells will quickly mutate into a form that enables them to process lactose: the mutation is then inherited by subsequent generations. Organisms don’t just passively wait, then, for a lucky accident or resign themselves to dying out, but actively remodel themselves in response to changes in their environment. As mentioned, changes in DNA are no longer thought to be mere accidents. Indeed Darwin himself wrote:

I have hitherto sometimes spoken as if the variations … were due to chance. This, of course is a wholly incorrect expression … Some authors believe it to be as much the function of the reproductive system to produce individual differences, or slight deviations of structure, as to make the child like its parents.

Another idea that perhaps does not square too well with the idea of genes bent on preserving themselves at all costs.

When developmental defects were artificially induced in a tadpole, subsequent development was able to adjust accordingly, apparently making corrections towards what it seemed to sense was its ultimate goal, the adult frog’s face, despite there being no ‘programme’ or previously known mechanism to direct it. Michael Levin, a prominent developmental biologist and geneticist at Tufts, writes:

Most organs were still placed into the right final positions, using movements quite unlike the normal events of metamorphosis, showing that what is encoded is not a hardwired set of tissue movements but rather a flexible, dynamic program that is able to recognize deviations, perform appropriate actions to minimize those deviations, and stop rearranging at the right time.

The question is ‘where is the information?’ That is to say, the in-form-ation. Where is the overall form or shape of the being stored, as a whole, in service of which any mechanisms we might detect and measure would be acting?

If any reader should be interested, there are a number of conversations between myself and Professor Michael Levin already up on YouTube. Our next conversation will be on March 3rd and will go up soon after. Finally thanks to my friend Caroline Ross for helping me get to grips with this alien technology. She has a wonderful Substack, and if I knew how to link to it, I would.

And please feel free to comment!

Just a few years ago, your book 'The Master & His Emissary' had an incredible impact on my life. Perhaps you won't mind a little backstory about this. At age 53 I left a cruelly oppressive place. And so I had to decide how to make a living. I had a good offer for a well-paid medical secretary job, or, I could try to build myself a small business of teaching art to adults. I followed my heart and chose the art. I realized that I would likely never be able to retire with that career choice. The art business grew slowly but steadily, and I was always able to pay for rent and groceries. However, I was prone to bouts of severe depression because of my past. (No one knew. I hid it well.) Then there came a time when I looked at some folks close to me who work with the homeless or on behalf of others who are downtrodden. Meanwhile, I thought to myself, I teach adults to paint and draw - tough job but someone has to do it. I deeply questioned the value of what I do. Then I came across your book. It told me that when I encourage people to be more creative, creativity can influence and increase their empathy for others! Your writing lifted my spirits with profound encouragement at a dark time for me. To me, it was a gift from God. And so here I am, 20 years later still teaching art and loving it, and so grateful. I am also grateful for the chance to say thank you - with all my heart. Thank you. I will not forget what your writing meant to me.

Wonderful to read you on here at last, my friend. Guess our next Zoom is about '@ mentions' so that you can mention your fellow writers more easily!